skeleton

Overview

This project is merged with skeleton. What is skeleton? It’s the scaffolding of a Python project jaraco introduced in this blog. It seeks to provide a means to re-use techniques and inherit advances when managing projects for distribution.

An SCM-Managed Approach

While maintaining dozens of projects in PyPI, jaraco derives best practices for project distribution and publishes them in the skeleton repo, a Git repo capturing the evolution and culmination of these best practices.

It’s intended to be used by a new or existing project to adopt these practices and honed and proven techniques. Adopters are encouraged to use the project directly and maintain a small deviation from the technique, make their own fork for more substantial changes unique to their environment or preferences, simply adopt the skeleton once and abandon it thereafter, or use it as a reference from which to cherry-pick ideas.

The primary advantage to using an SCM for maintaining these techniques is that those tools help facilitate the merge between the template and its adopting projects.

Another advantage to using an SCM-managed approach is that tools like GitHub recognize that a change in the skeleton is the same change across all projects that merge with that skeleton. Without the ancestry, with a traditional copy/paste approach, a commit like this would produce notifications in the upstream project issue for each and every application, but because it’s centralized, GitHub provides just the one notification when the change (and its commit hash) is added to the skeleton.

Yet another advantage is the ability to manage common concerns in a common repo. Concerns that apply to the best practices or other concerns managed by skeleton can be filed, tracked, and resolved in the skeleton issue tracker.

Usage

new projects

To use skeleton for a new project, simply pull the skeleton into a new project:

$ git init my-new-project

$ cd my-new-project

$ git pull gh://jaraco/skeleton

Now customize the project to suit your individual project needs.

In particular, make some replacements:

PROJECT: name of the project in PYPIPROJECT_PATH: org/name of the project in GithubPROJECT_DESCRIPTION: a description of the projectPROJECT_RTD: (optional) the RTD-mangled name of the project

existing projects

If starting from an existing project, incorporate the skeleton by merging it into the codebase.

$ git merge skeleton --allow-unrelated-histories

The --allow-unrelated-histories is necessary on the first merge because the history from the skeleton was previously unrelated to the existing codebase. Resolve any merge conflicts and commit to the master, and thereafter the project is based on the shared skeleton.

Updating

Whenever a change is needed or desired for the general technique for packaging, it can be made in the skeleton project and then merged into each of the derived projects as needed, recommended before each release. As a result, features and best practices for packaging are centrally maintained and readily trickle into a whole suite of packages. This technique lowers the amount of tedious work necessary to create or maintain a project, and coupled with other techniques like continuous integration and deployment, lowers the cost of creating and maintaining refined Python projects to just a few, familiar Git operations.

For example, here’s a session of the path project pulling non-conflicting changes from the skeleton:

Additionally, the author maintains a routine to mechanically apply the changes from the skeleton or other “upstream” bases.

Thereafter, the target project can make whatever customizations it deems relevant to the scaffolding. The project may even at some point decide that the divergence is too great to merit renewed merging with the original skeleton. This approach applies maximal guidance while creating minimal constraints.

Periodic Collapse

In late 2020, this project introduced the idea of a periodic but infrequent (O(years)) collapse of commits to limit the number of commits a new consumer will need to accept to adopt the skeleton.

The full history of commits is collapsed into a single commit and that commit becomes the new mainline head.

When one of these collapse operations happens, any project that previously pulled from the skeleton will no longer have a related history with that new main branch. For those projects, the skeleton provides a “handoff” branch that reconciles the two branches. Any project that has previously merged with the skeleton but now gets an error “fatal: refusing to merge unrelated histories” should instead use the handoff branch once to incorporate the new main branch.

$ git pull https://github.com/jaraco/skeleton 2020-handoff

This handoff needs to be pulled just once and thereafter the project can pull from the main head.

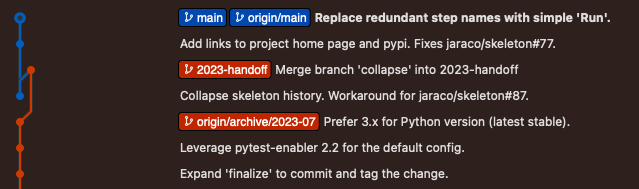

Here’s what the tree looks like following a handoff:

The update-projects routine may be used to apply this project to existing projects:

py -m jaraco.develop.update-projects --branch 2023-handoff

The archive and handoff branches from prior collapses are indicate here:

| refresh | archive | handoff |

|---|---|---|

| 2020-12 | archive/2020-12 | 2020-handoff |

| 2023-07 | archive/2023-07 | 2023-handoff |

Features

The features/techniques employed by the skeleton include:

- PEP 517/518-based build relying on Setuptools as the build tool

- Setuptools declarative configuration using pyproject.toml

- tox for running tests

- A README.rst as reStructuredText with some popular badges, but with Read the Docs badges commented out

- A CHANGES.rst file intended for publishing release notes about the project

- Use of Ruff for linting and formatting

- Integrated type checking through mypy

- Dependabot enabled to enable supply chain security

- Use of diff-cover to encourage test coverage

Packaging Conventions

A pyproject.toml is included and implements the following features:

- Enable PEP 517 and PEP 518 to build the project on Setuptools.

- Reads the README.rst file into the long description

- Some common Trove classifiers

- Includes all packages discovered in the repo

- Data files in the package are also included (not just Python files)

- Declares the required Python versions

- Declares install requirements (empty by default)

- Supplies two sets of “optional dependencies”:

- test: requirements for running tests

- doc: requirements for building docs

- these dependencies (sometimes called “extras”) split the declaration into “upstream” (requirements as declared by the skeleton) and “local” (those specific to the local project); these markers help avoid merge conflicts

- Placeholder for defining entry points

Additionally, the pyproject.toml file declares [tool.setuptools_scm], which enables setuptools_scm to do two things:

- derive the project version from SCM tags

- ensure that all files committed to the repo are automatically included in releases

Compatibility Modules

Projects relying on skeleton are advised to organise their own internal

polyfills, backports, workarounds and version conditional imports into a

series of separated modules under the compat subpackage.

These modules provide compatibility layers or shims and often ensure code runs

smoothly across different Python versions.

Examples of such practice include keyring.compat, zipp.compat, and setuptools.compat.

In the case of shims and conditional imports that depend on specific versions

of the interpreter, the module name should reflect the Python version that requires the

legacy behavior. For example, the module setuptools.compat.py312 supports

compatibility with Python 3.12 and earlier.

This naming convention is beneficial because it signals when the code

can be removed. When support for Python 3.12 is dropped

(i.e., when requires-python = ">=3.13" is added to pyproject.toml),

imports of the module py312 will be easily identifiable as removable debt.

Please note that these modules are implementation details and - unless explicitly documented otherwise by each particular project - not part of the public API.

Running Tests

The skeleton assumes the developer has tox installed. The developer is expected to run tox to run tests on the current Python version using pytest.

The test suite is configured not only to run the project’s tests as discovered by pytest, but also includes several plugins to perform other checks:

pytest-ruffperforms lint and formatting checks using ruffpytest-mypyperforms type checks using mypypytest-checkdocsensures that the README renders without errorspytest-covreports the coverage of the project

Many of these plugins are enabled through pytest-enabler to allow easy disablement of any one of them. Simply pass -p no:{plugin} (e.g. -p no:cov) to pytest (e.g. tox -- -p no:cov) to disable the plugin for that run.

Other environments (invoked with tox -e {name}) are available. Use tox list for a description of each.

A pytest.ini is included to define common options around running tests. In particular:

- rely on default test discovery in the current directory

- avoid recursing into common directories not containing tests

- run doctests on modules and invoke Ruff tests

- filters out known warnings caused by libraries/functionality included by the skeleton

These checks are non-invasive; they don’t automatically modify the code, but merely report on violations. Correct the violations manually or consider running the relevant tools (e.g. ruff format . or ruff check --fix .). A pre-commit config exists, but due to maintenance challenges is unsupported (use at your own risk).

Continuous Integration

The project is pre-configured to run Continuous Integration tests.

Github Actions

Github Actions are the preferred provider as they provide free, fast, multi-platform services with straightforward configuration. Configured in .github/workflows.

Features include:

- test against multiple Python versions

- run on late (and updated) platform versions

- automated releases of tagged commits

- automatic merging of PRs (requires protecting branches with required status checks, not possible through API)

- unpinned actions

- efficient resource consumption

Continuous Deployments

In addition to running tests, an additional publish stage is configured to automatically release tagged commits to PyPI using API tokens. The release process expects an authorized token to be configured with each Github project (or org) PYPI_TOKEN secret. Example:

pip-run jaraco.develop -- -m jaraco.develop.add-github-secrets

Building Documentation

Documentation is automatically built by Read the Docs when the project is registered with it, by way of the .readthedocs.yml file. To test the docs build manually, a tox env may be invoked as tox -e docs. Both techniques rely on the dependencies declared in pyproject.toml/project.optional-dependencies.doc.

In addition to building the Sphinx docs scaffolded in docs/, the docs build a history.html file that first injects release dates and hyperlinks into the CHANGES.rst before incorporating it as history in the docs.

Cutting releases

By default, tagged commits are released through the continuous integration deploy stage.

Releases may also be cut manually by invoking the tox environment release with the PyPI token set as the TWINE_PASSWORD:

TWINE_PASSWORD={token} tox -e release

Ignoring Artifacts

This project does not include a .gitignore module or provides a very minimal one because this project holds the philosophy that it’s preferable to specify ignores at the most relevant level, and so .gitignore for a project should specify elements unique to that project and not elements peculiar to the language or system or user.

Instead, skeleton recommends users to implement ignores for the language(s), system, and user in the development environment. For example, jaraco has the following in ~/.gitconfig:

[core]

excludesfile = ~/.gitignore_global

Referencing this .gitignore_global.

As you can see, this file contains all of the commonly encountered ignorables when developing node.js and Python projects using PyCharm or emacs or git on all the common platforms. This simple configuration, linked in each development environment, avoids the need to configure (and sync) each downstream project with the aggregate configuration of jaraco’s environments and the environments of each of the contributors to each of the projects the contributiors may touch.

It’s not a perfect alignment of concerns to projects, but it’s a dramatically simpler approach saving hundreds of commits that can be readily adopted by any user and is strongly recommended for skeleton-based projects.

See gitignore docs for more details regarding configuring ignore files. For users only incidentally involved with skeleton-derived projects, consider downloading jaraco’s .gitignore_global to the checked-out project:

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jaraco/dotfiles/main/.gitignore_global -O - >> .git/info/exclude

Note: See dotfiles for guidance on applying these settings in GitHub Codespaces.

Challenges

Because this approach applies concerns across repos, it does violate some assumptions leading to undesirable outcomes.

History is Forever

The history accumulates and each project that adopts it gets the full history. Even a brand new project will get commits going back as far as the main history goes. As a result, cruft accumulates and multiplies across projects.

The Periodic Collapse mentioned above attempts to alleviate this pressure by occasionally (rarely) collapsing the history, but this approach adds its own downsides:

- the true history is obscured

- existing histories are broken until the handoff commit is pulled

- attribution is lost

Continuous Integration Mismatch

Because CI instructions for “best practices” are stored in the repo, it’s not possible to supply CI instructions for both:

- downstream projects, and

- the skeleton itself.

Best case, the tests in the skeleton repo are degenerate and pass. Worst case, the tests fail because they rely on factors expected to be supplied downstream (e.g. doc builds currently fail because they rely on the root package name being supplied to be documented).

Moreover, it’s not viable to test aspects specific to the skeleton that should not appear/apply downstream, such as to check that commit messages in the skeleton meet certain criteria.

Commit Integrations Mismatch

Github has some nice features to link mentions in commits to issues and pull requests, including taking actions such as closing issues. When applying commits from the skeleton that mention fixing a common concern can unintentionally affect downstream projects unless the committer is careful to use project-absolute references (e.g. “jaraco/skeleton#27” vs. “#27”).